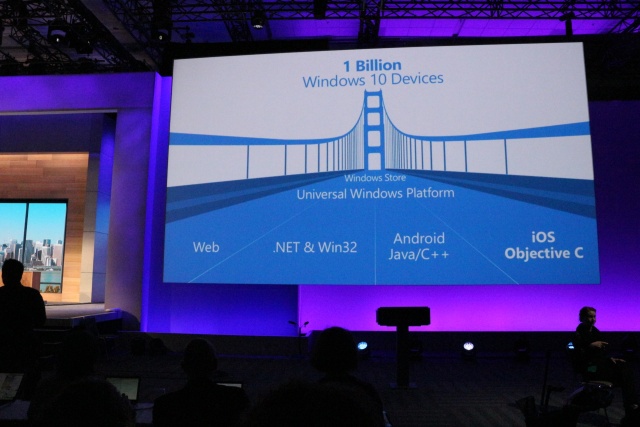

At its Build developer conference last week, Microsoft made a pair of announcements about Windows development that were more than a little surprising: Windows will support applications developed for iOS and Android.

This immediately felt like a dangerous move. Windows will not be the first operating system to run foreign applications. Famously, IBM advertised OS/2 as a “Better Windows than Windows” in the 1990s, boasting that its platform would run all your existing Windows applications with greater stability and performance. More recently, BlackBerry 10 included support for Android applications, with BlackBerry licensing the Amazon App Store and using it as its gateway to a world of Android-compatible software.

Neither OS/2 nor BlackBerry 10 has made a success of this capability. There are two major problems with supporting foreign applications on a niche platform. The first is straightforward: it removes any incentive for developers to bother with the native platform. Investing in developing for a minor platform is already something of a gamble, and by telling developers “Oh hey, you can just use your existing Win16 or Android program…” as IBM and BlackBerry (respectively) did, you’re implicitly sending them a message. “Don’t bother learning our platform or writing native apps for it.”

It turned out as expected for both platforms. While a few true OS/2 applications were created—and similarly there are some true BlackBerry 10 apps—they’re relatively unusual. After all, what’s the point? If IBM is going to boast about just how well OS/2 will run Win16 apps and those Win16 apps can be sold both to OS/2 users and to Windows 3.1 users, why would a developer write anything other than a Win16 app?

This capability cedes a lot of control. By being dependent on apps developed for a third-party platform, you give the owner of that third-party platform the power to choose how to evolve its APIs and add new features. This bit OS/2 hard: while IBM was busy promoting how well OS/2 could run 16-bit Windows applications, Microsoft was busy encouraging developers to create new 32-bit Windows applications and end-users to buy the 32-bit capable Windows 95. This new world of 32-bit software wouldn’t run on OS/2, and so the big OS/2 feature that IBM heavily marketed was rendered semi-useless. OS/2 found some niche success, but it was ultimately a failure.

Supporting Android apps creates similar risks. If Android software constitutes a major part of a platform’s software ecosystem, any changes to Android (new APIs or capabilities, say) that Android software expects to be able to take advantage of have to be replicated. This is, however, tempered by Android’s uniquely poor update situation. Most Android phones don’t have access to the latest and greatest version of Android or the latest and greatest Android features, so most Android software has to refrain from demanding such capabilities. This means an Android-compatible platform could trail Google’s cutting edge by a year or more and still be highly compatible with Android apps.

Read More: Android and iOS apps on Windows: What is Microsoft doing—and will it work? | Ars Technica.