AMD Radeon Vega Is Here!!!! Intel’s 545S… an affordable SSD, Samsung Galaxy S8+ and OnePlus 5 reviews… and mining specific GPUs. That’s a thing now! All that and more in This Week In Computer Hardware episode 421!

Tag Archives: gpu

Some DirectX 12 features will require next-gen graphics hardware

Earlier in the week, at the Game Developers Conference, Microsoft unveiled DirectX 12, the next version of the company’s widely-used graphics API. One major feature of DirectX 12 is lower-level abstraction; that is, game developers will have better access to graphics hardware with improved utilization of the CPU. This feature will be available across nearly all current-generation GPUs from both AMD and Nvidia.

However DirectX 12 isn’t just a one trick pony. To get the full array of features that will come with the new API, you’ll need new graphics hardware, just like with previous DirectX iterations. Two features for new hardware that have been revealed are new blend modes and conservative rasterization, but according to Microsoft, there’s still a few more features to be revealed.

It’ll be interesting to see how long it takes game developers to implement the features of DirectX 12 that require new hardware. DirectX 11 was released alongside Windows 7 back in 2009, but it took several years for the API level to see widespread inclusion in PC games. This could be due to the lack of DirectX 11 support in consoles of the time, which won’t be a factor this time around as the Xbox One will support DirectX 12.

A preview of DirectX 12 will be released later this year, when all the features of the API will come to light. Games using DirectX 12 are still quite some time away though, with Microsoft estimating that we’ll first see it in holiday-season games in 2015.

via Some DirectX 12 features will require next-gen graphics hardware – TechSpot.

Nvidia quietly launches Titan Black graphics card, rolls out new GeForce drivers

Nvidia’s flagship Titan graphics card quietly received a refresher today with the launch of the Titan Black. I say quiet because Nvidia didn’t even publish a press release on the matter (a blog post got the job done), instead electing to focus their attention on the new Maxwell architecture.

Nevertheless, the new Titan Black is here and it features modest updates across the board (no pun intended). The clock speed is up from 837MHz to 889MHz, boost clock is now at 980MHz versus 876MHz on the original Titan and the 6GB of 384-bit GDDR5 memory now operates at 7GHz instead of 6GHz. The stream processor count is also a tad bit higher, too, at 2880 versus 2688 from last year.

The card is available starting today for $999, the same price the original Titan launched at.

In related news, Nvidia also rolled out new GPU drivers. Version 334.89 WHQL are said to boost performance by as much as 19 percent in F1 2013, up to 18 percent in Sleeping Dogs, up to 16 percent in Hitman Absolution and up to 15 percent in Company of Heroes 2.

The new drivers also include new SLI profiles for Assassin’s Creed Liberation HD, Assassin’s Creed: Freedom Cry, Deus Ex: Human Revolution Director’s Cut and The Crew. Additionally, Nvidia has included new 3D Vision profiles for Shadow Warrior, The Stanley Parable, Walking Dead 2, World Rally Championship 4, LEGO Marvel Super Heroes, and Far Cry 3 Blood Dragon.

via Nvidia quietly launches Titan Black graphics card, rolls out new GeForce drivers – TechSpot.

Nvidia slashes GeForce GTX 780, 770 prices as it preps for GTX 780 Ti launch

Earlier today we reported that Nvidia has added ShadowPlay support to its GeForce Experience software and now we are hearing the GPU maker has slashed the price of some of their high-end GTX 700-series graphics cards and announced a release date for the GTX 780 Ti. Busy day at Nvidia, eh?

The suggested retail price for the GeForce GTX 780 will dropped from $649 to $499 while the GTX 770 will soon sell for $329 versus the previous $399 asking price. The cuts are expected to go into effect starting at 6 a.m. on October 29 so if you are in the market for either of these cards, just wait a day and save yourself enough money to buy some new games on Nvidia’s dime.

The price breaks will position Nvidia’s top cards to better compete with new Radeon hardware from AMD. For example, the GTX 780 will soon serve as a solid alternative to the R9 290X GPU in terms of performance for the dollar. And if that weren’t enough, the GTX 780 and 770 also ship with a free copy of Assassin’s Creed IV: Black Flag, Batman: Arkham Origins and Splinter Cell: Blacklist and a $100 off coupon for a Shield handheld gaming system.

Elsewhere, Nvidia said the GTX 780 Ti (expected to be a faster version of the GTX Titan) will arrive on November 7 priced at $699 and will ship with the same games bundle and Shield coupon as the GTX 780 and 770.

via Nvidia slashes GeForce GTX 780, 770 prices as it preps for GTX 780 Ti launch – TechSpot.

Microsoft: “System processing” takes up 10 percent of Xbox One GPU time

The Xbox One’s ability to run up to four apps in the background (or on the side via Snap mode) during gameplay and to switch from a game to those apps almost instantaneously obviously comes at some cost to the system’s maximum theoretical gaming performance. Now, thanks to an interview with Xbox technical fellow Andrew Goossen over at Digital Foundry we have some idea of the scale of that performance cost.

“Xbox One has a conservative 10 percent time-sliced reservation on the GPU for system processing,” Goossen told the site. “This is used both for the GPGPU processing for Kinect and for the rendering of concurrent system content such as snap mode.”

It’s important to note that additional processing time for the next-generation Kinect sensor is included in that 10 percent number. Still, setting aside nearly a tenth of the GPU’s processing time to support background execution of non-gaming apps is a bit surprising.

During a recent demonstration of the Xbox One interface, Microsoft Director of Product Planning Albert Penello showed me how running multiple apps on the side or behind a concurrent game didn’t lead to any noticeable degradation in gaming performance. Indeed, setting aside a good chunk of GPU processing to explicitly handle nongaming apps ensures that gaming performance doesn’t bounce up and down depending on what may or may not be running in the background.

The downside, of course, is that developers are unable to use that reserved chunk of processing power. Not to worry, though; Goossen says that Microsoft plans to open up this power to developers in the future in a way that doesn’t impact the system’s background functions.

“The GPU hardware scheduler is designed to maximize throughput and automatically fills ‘holes’ in the high-priority processing,” Goossen said. “This can allow the system rendering to make use of the ROPs for fill, for example, while the title is simultaneously doing synchronous compute operations on the compute units.”

Sony’s PlayStation 4 also allows for non-gaming apps to run in the background while games are playing and for instant switching between these apps, but the company has not gone into detail about what kind of impact this functionality has on the system’s processing load.

Digital Foundry also has more from a wide-ranging interview with Goossen and Xbox hardware architect Nick Baker, touching on everything from RAM bandwidth and pixel shading to compute units and clock speed. It’s well worth a read for anyone looking for a deep dive into the raw hardware power of Microsoft’s next system.

via Microsoft: “System processing” takes up 10 percent of Xbox One GPU time | Ars Technica.

AMD next-gen Radeon 'Hawaii' graphics cards expected in October

AMD is reportedly preparing to mass ship their next generation high-end GPU codenamed Hawaii in October according to sources in the upstream supply chain as reported by DigiTimes. When you consider AMD is flying a number of journalists to Hawaii (no coincidence there) late next month for a “technical showcase,” this rumor quickly becomes much more credible.

A hard launch coming a couple of weeks after this technical showcases makes sense as it would give journalists and reviewers plenty of time to thoroughly test hardware. That’s been the pattern for both AMD and Nvidia in the past but then again, the source doesn’t mention when specifically in October cards would ship. It could be October 1 or October 31 and if it’s the latter, that means availability could be scarce through November. Either way, however, parts should be available in time for the holiday buying season.

Specifically, DigiTimes believes Asus, MSI and PowerColor will be among the first to ship Hawaii-based products. The company is already cutting prices for its Radeon HD 7000 series cards including the HD 7990.

Word dropped earlier this month that AMD would unveil Hawaii-based GPUs in the Aloha State on September 25. Not much else is known about the event or what the Hawaii GPU has in store other than it is expected to compete against Nvidia’s top-end offering in the $600 price range. A leaked benchmark showed the card could be faster than Nvidia’s GTX Titan, at least in 3DMark 11.

via AMD next-gen Radeon ‘Hawaii’ graphics cards expected in October – TechSpot.

$1100 MSI laptop packs Radeon HD 8970M, AMD claims fastest mobile GPU

In 2012, AMD began shipping its mobile line-up of Radeon HD 8000M-series just in time for the arrival of 2013. AMD unveiled today the latest addition to that mobile GPU family, its upcoming series of Radeon HD 8900M chips.

The Radeon 8900M-series flagship, the 8970M, packs twice the number of stream processors found in its 8870M counterpart, giving it a total of 1280 stream processors (or 20 compute units). AMD’s newest mobile powerhouse also boasts a speedier memory bus (GDDR5 @ 1.2GHz) and higher-clocked graphics core (850MHz).

In case you’re curious to compare, the desktop variant of the HD 8970 (pdf) is expected to feature 2048 stream processors and a 1.5GHz memory bus. As mobile versions often are, the 8970M is scaled down from its a bigger brother but still remains a remarkable piece of equipment to cram inside a laptop-sized portable.

According to AMD’s own benchmarks, its Radeon HD 8900M is up to 54 percent faster than Nvidia’s best mobile offering, the Geforce GTX 680M. Of course, don’t expect such claims to be based on entirely impartial testing though — you can bet AMD probably isn’t showing its worst results.

Coordinating with AMD’s announcement, MSI will be launching a rejiggered line of GX70 laptops. GX70s destined to house AMD’s highest-end mobile GPU are expected to arrive as soon as next month. The nearly nine-pound laptop will also come equipped with AMD’s fastest Richland-based A10-5750M APU, a matte 17.3″ 1080p display and a 7800mAH battery pack. One of the best features of this laptop has to be its price though: about $1100 MSRP.

via $1100 MSI laptop packs Radeon HD 8970M, AMD claims fastest mobile GPU – TechSpot.

History of the Modern Graphics Processor, Part 4

The Coming of General Purpose GPUs

Until the advent of DirectX 10, there was no point in adding undue complexity by enlarging the die area, which increased vertex shader functionality in addition to boosting the floating point precision of pixel shaders from 24-bit to 32-bit to match the requirement for vertex operations. With DX10’s arrival, vertex and pixel shaders maintained a large level of common function, so moving to a unified shader arch eliminated a lot of unnecessary duplication of processing blocks. The first GPU to utilize this architecture was Nvidia’s iconic G80.

Four years in development and $475 million produced a 681 million-transistor, 484mm² behemoth — first as the 8800 GTX flagship and 8800 GTS 640MB on November 8. An overclocked GTX, the 8800 Ultra, represented the G80’s pinnacle and was sandwiched between the launches of two lesser products: the 320MB GTS in February and the limited production GTS 640MB/112 Core on November 19, 2007.

Aided by the new Coverage Sample anti-aliasing (CSAA) algorithm, Nvidia had the satisfaction of seeing its GTX demolish every single and dual-graphics competitor in outright performance. Despite that success, the company dropped three percentage points in discrete graphics market share in the fourth quarter — points AMD picked up on the strength of OEM contracts.

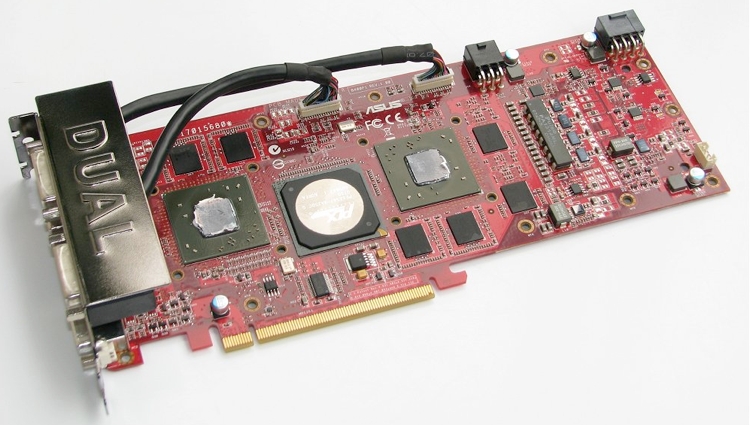

MSI’s version of the GeForce 8800 GTX

The remaining components of Nvidia’s business strategy concerning the G80 became reality in February and June of 2007. The C-language based CUDA platform SDK (Software Development Kit) was released in beta form to enable an ecosystem leveraging the highly parallelized nature of GPUs. Nvidia’s PhysX physics engine as well as its distributed computing projects, professional virtualization and OptiX, Nvidia’s ray tracing engine, are the more high profile applications using CUDA.

Both Nvidia and ATI (now AMD) had been integrating ever-increasing computing functionality into the graphics pipeline. ATI/AMD would choose to rely upon developers and committees for the OpenCL path, while Nvidia had more immediate plans in mind with CUDA and high performance computing.

To this end, Nvidia introduced its Tesla line of math co-processors in June, initially based on the same G80 core that had already powered the GeForce and Quadro FX 4600/5600, and after a prolonged development that included at least two (and possibly three) major debugging exercises, AMD released the R600 in May.

Aided by the new Coverage Sample anti-aliasing (CSAA) algorithm, Nvidia had the satisfaction of seeing its GTX demolish every single and dual-graphics competitor in outright performance.

Media hype made the launch hotly anticipated as AMD’s answer to the 8800 GTX, but what arrived as the HD 2900 XT was largely disappointing. It was an upper-midrange card allied with the power usage of an enthusiast board, consuming more power than any other contemporary solution.

The scale of the R600 misstep had profound implications within ATI, prompting strategy changes to meet future deadlines and maximize launch opportunities. Execution improved with RV770 (Evergreen) as well as the Northern and Southern Islands series.

Along with being the largest ATI/AMD GPU to date at 420mm², R600 incorporated a number of GPU firsts. It was AMD’s first DirectX 10 chip, its first and only GPU with a 512-bit memory bus, first vendor desktop chip with a tessellator unit (which remained largely unused thanks to game developer indifference and a lack of DirectX support), first GPU with integrated audio over HDMI support, as well as its first to use VLIW, an architecture that has remained with AMD until the present 8000 series. It also marked the first time since the Radeon 7500 that ATI/AMD hadn’t fielded a top tier card in relation to the competition’s price and performance.

AMD updated the R600 to the RV670 by shrinking the GPU from TSMC’s 80nm process to a 55nm node in addition to replacing the 512-bit bidirectional memory ring bus with a more standard 256-bit. This halved the R600’s die area while packing nearly as many transistors (666 million versus 700 million in the R600). AMD also updated the GPU for DX10.1 and added PCI Express 2.0 support, all of which was good enough to scrap the HD 2000 series and compete with the mainstream GeForce 8800 GT and other lesser cards.

In the absence of a high-end GPU, AMD launched two dual-GPU cards along with budget RV620/635-based cards in January 2008. The HD 3850 X2 shipped in April and the final All-In-Wonder branded card, the HD 3650, in June. Released with a polished driver package, the dual GPU cards made an immediate impact with reviewers and the buying public. The HD 3870 X2 comfortably became the single fastest card and the HD 3850 X2 wasn’t a great deal slower. Unlike Nvidia’s SLI solution, AMD instituted support for Crossfiring cards with a common ASIC.

Full Story: History of the Modern Graphics Processor, Part 4 – TechSpot.

History of the Modern Graphics Processor, Part 3

The Fall of 3Dfx and The Rise of Two Giants

With the turn of the century the graphics industry bore witness to further consolidation.

The pro market saw iXMICRO leave graphics entirely, while NEC and Hewlett-Packard both produced their last products, the TE5 and VISUALIZE FX10 series respectively. Evans & Sutherland also parted ways with the sale of its RealVision line to focus on the planetaria and fulldome projection systems.

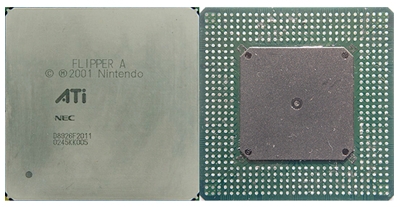

In the consumer graphics market, ATI announced the acquisition of ArtX Inc. in February 2000, for around $400 million in stock. ArtX was developing the GPU codenamed Project Dolphin (eventually named “Flipper”) for the Nintendo GameCube, which added significantly to ATI’s bottom line.

ATI GameCube GPU

Also in February, 3dfx announced a 20% workforce cut, then promptly moved to acquire Gigapixel for $186 million and gained the company’s tile-based rendering IP.

Meanwhile, S3 and Nvidia settled their outstanding patent suits and signed a seven-year cross-license agreement.

VIA assumed control of S3 around April-May which itself was just finishing a restructuring process from the acquisition of Number Nine. As part of S3’s restructuring, the company merged with Diamond Multimedia in a stock swap valued at $165 million. Diamond’s high-end professional graphics division, FireGL, was spun off as SONICblue and later sold to ATI in March 2001 for $10 million.

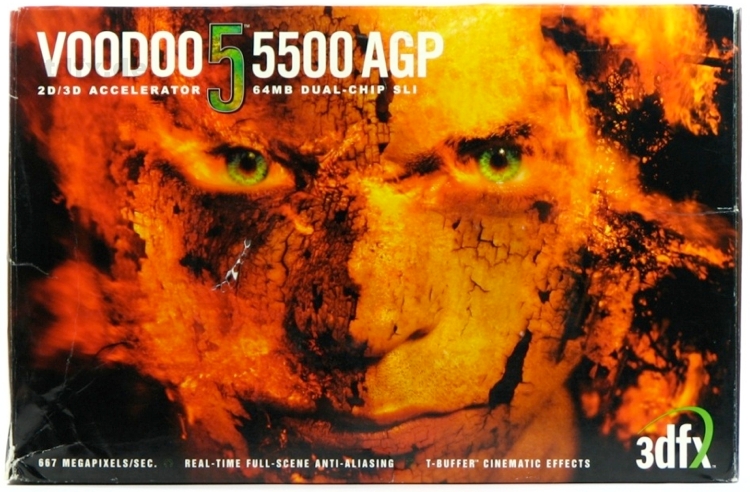

3DLabs acquired Intergraph’s Intense3D in April, while the final acts of 3dfx played out towards the end of the year, despite 2000 kicking off with the promise of a better future as the long-awaited Voodoo 5 5500 neared its debut in July. The latter ended up trading blows with the GeForce 256 DDR and won the high-resolution battle.

Where 3dfx was once a byword for raw performance, its strengths around this time laid in its full screen antialiasing image quality.

But where 3dfx was once a byword for raw performance, its strengths around this time laid in its full screen antialiasing image quality. The Voodoo 5 introduced T-buffer technology as an alternative to transformation and lighting, by basically taking a few rendered frames and aggregating them into one image. This produced a slightly blurred picture that, when run in frame sequence, smoothed out the motion of the animation.

3dfx’s technology became the forerunner of many image quality enhancements seen today, like soft shadows and reflections, motion blur, as well as depth of field blurring.

3dfx’s swan song, the Voodoo 4 4500, arrived October 19 after several delays – unlike the 4200 and 4800 that were never released. The card was originally scheduled for spring as a competitor to Nvidia’s TNT2, but ended up going against the company’s iconic GeForce 256 DDR instead, as well as the much better performing GeForce 2 GTS and ATI Radeon DDR.

On November 14, 3dfx announced they were belatedly ceasing production and sale of their own-branded graphics cards, something that had been rumoured for some time but largely discounted. Adding fuel to the fire, news got out that upcoming Pentium 4 motherboards would not support the 3.3V AGP signalling required Voodoo 5 series.

Voodoo5 5500 AGP box art

The death knell sounded a month later for 3dfx when Nvidia purchased its IP portfolio for $70 million plus one million shares of common stock. A few internet wits later noted that the 3dfx design team which had moved to Nvidia eventually got both their revenge and lived up to their potential, by delivering the underperforming NV30 graphics chip powering the FX 5700 and FX 5800 cards behind schedule.

Full Story: History of the Modern Graphics Processor, Part 3 – TechSpot.

History of the Modern Graphics Processor, Part 2

3Dfx Voodoo: The Game-changer

Launched on November 1996, 3Dfx’s Voodoo graphics consisted of a 3D-only card that required a VGA cable pass-through from a separate 2D card to the Voodoo, which then connected to the display.

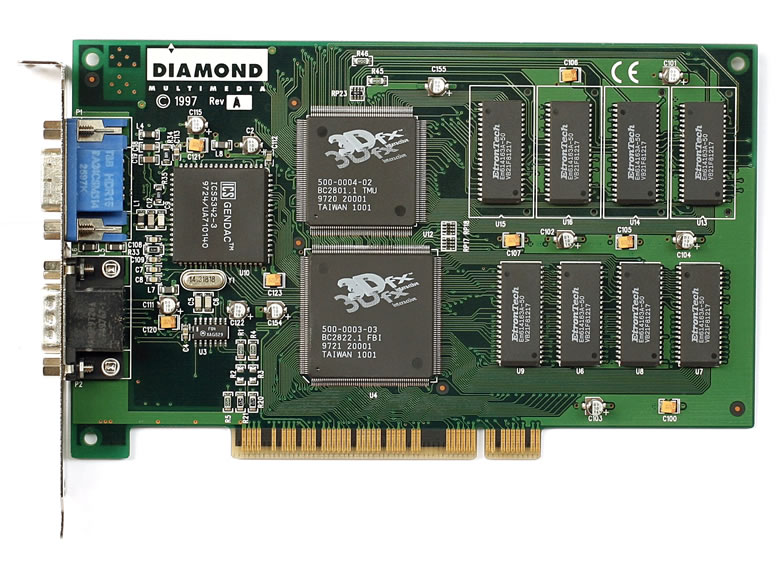

The cards were sold by a large number of companies. Orchid Technologies was first to market with the $299 Orchid Righteous 3D, a board noted for having mechanical relays that “clicked” when the chipset was in use. Later revisions utilized solid-state relays in line with the rest of the vendors. The card was followed by Diamond Multimedia’s Monster 3D, Colormaster’s Voodoo Mania, the Canopus Pure3D, Quantum3D, Miro Hiscore, Skywell (Magic3D), and the 2theMAX Fantasy FX Power 3D.

Voodoo Graphics revolutionized personal computer graphics nearly overnight and rendered many other designs obsolete, including a vast swathe of 2D-only graphics producers. The 3D landscape in 1996 favoured S3 with around 50% of the market. That was to change soon, however. It was estimated that 3Dfx accounted for 80-85% of the 3D accelerator market during the heyday of Voodoo’s reign.

Diamond Multimedia’s Monster 3D (3dfx Voodoo1 4MB PCI)

Around that time VideoLogic had developed a tile based deferred rendering technology (TBDR) which eliminated the need for large scale Z-buffering (removing occluded/hidden pixels in the final render) by discarding all but visible geometry before texture, shading and lighting were applied to that which remained. The frame resulting from this process was sectioned into rectangular tiles, each tile with its own polygons rendered and sent to output. Polygon rendering commenced once the pixels required for the frame were calculated and polygons culled (Z-buffering only occurred at tile level). This way only a bare minimum of calculation was required.

The first two series of chips and cards were built by NEC, while Series 3 (Kyro) chips were fabricated by ST Micro. The first card was used exclusively in Compaq Presario PCs and was known as the Midas 3 (the Midas 1 and 2 were prototypes for an arcade based system project). The PCX1 and PCX2 followed as OEM parts.

The 3D landscape in 1996 favoured S3 with around 50% of the market. That was to change soon, however. It was estimated that 3Dfx accounted for 80-85% of the 3D accelerator market during the heyday of Voodoo’s reign.

Series 2 chip production initially went to Sega’s Dreamcast console, and by the time the desktop Neon 250 card hit retail in November 1999, it was brutally outclassed at its $169 price range, particularly in higher resolutions with 32-bit color.

Just before the Neon 250 became available, Rendition’s Vérité V1000 became the first card with a programmable core to render 2D + 3D graphics, by utilizing a MIPS-based RISC processor as well as the pixel pipelines. The processor was responsible for triangle setup and organizing workload for the pipelines.

Originally developed towards the end of 1995, the Vérité 1000 became one of the boards that Microsoft used to develop Direct3D. Unfortunately, the card required a motherboard chipset capable of supporting direct memory access (DMA), since the Rendition used this method to transfer data across the PCI interface. The V1000 fared well in comparison with virtually every other consumer graphics board prior to the arrival of the Voodoo Graphics, which had more than double the 3D performance. The board was relatively cheap and offered a good feature set, including edge antialiasing for the budget gamer and hardware acceleration of id Software’s Quake. Game developers, however, shied away from the DMA transfer model all too soon for Rendition’s liking.

Full Story: History of the Modern Graphics Processor, Part 2 – TechSpot.